Portraits of Clément Marot

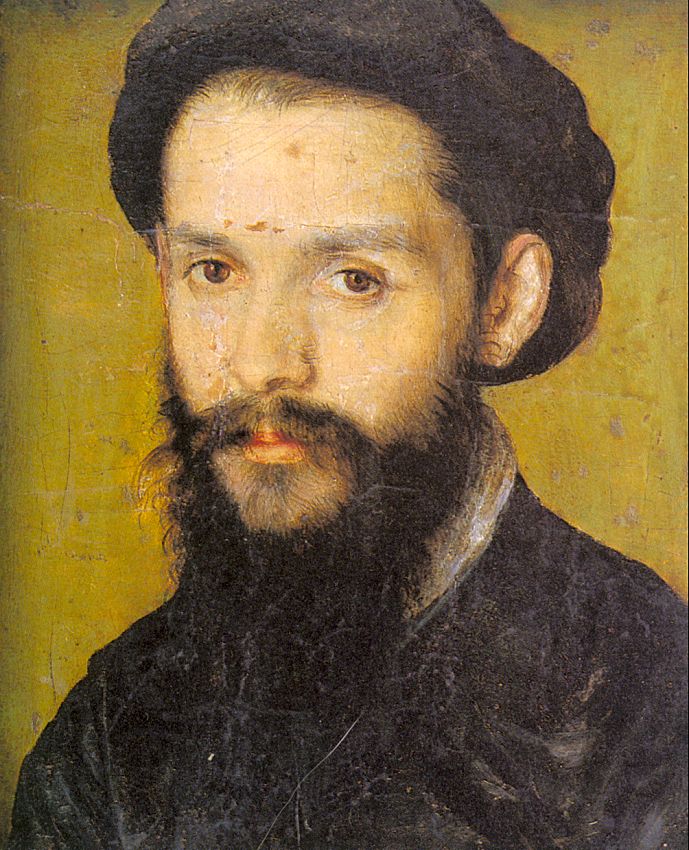

Hermitage – St Petersburg. INV: ОР-2979. Link

Surprise ! This quite unknown portrait – in the Hermitage – might very well be the most plausible candidate if you want to get an idea of how Marot really looked like ca. 1540. The date, the clothing and style are correct (the baret was in fashion then, and the dress fits a cleric or magistrate, remember: Marot was ‘valet de chambre’) The drawing was bought by Catharine the Great in 1768 together with a lot of other French Renaissance paintings (collection Cobenzl = more info below]. The annotation at the top (‘de Chambre du Roy ….. clement Marot poete valet’) is partly in a contemporary hand, and partly 18th century.

The more familiar portraits

1. Corneille de Lyon, portrait of a man (1540s)

In the past generally accepted to be Marot. Recent research questions this attribution: Marot was in Lyon in the second half of the 1530s, but the clothing suggests rather the second half of the 1540s. Marot died 1544. And he looks quite young here. A copy of this painting is in the museo civico in Piacenza. The portrait is quite small (12x10cm). The framing in the Louvre on the other hand…

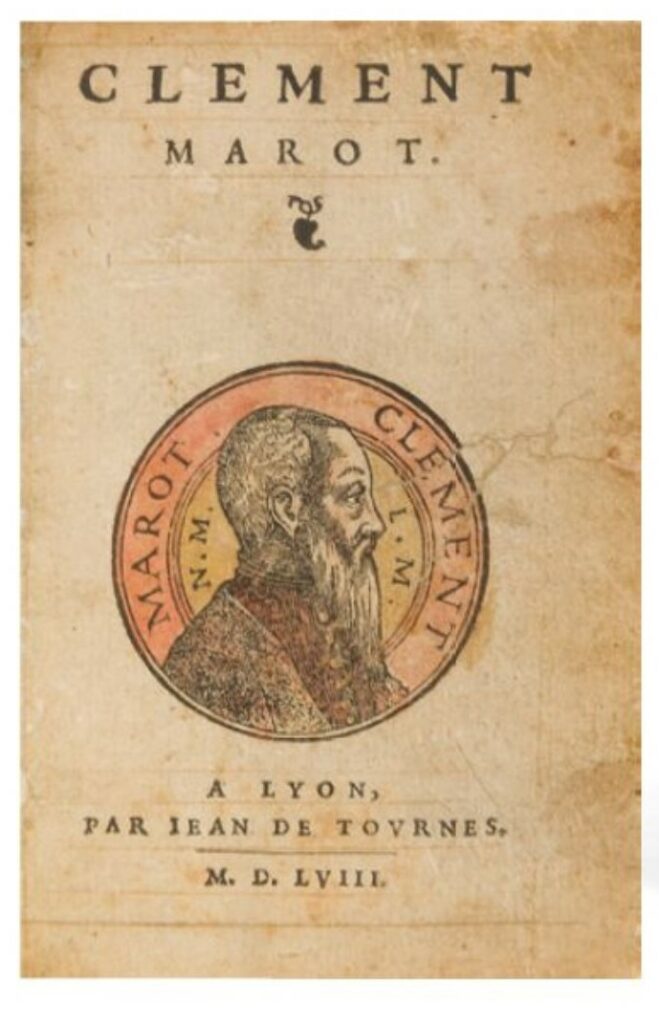

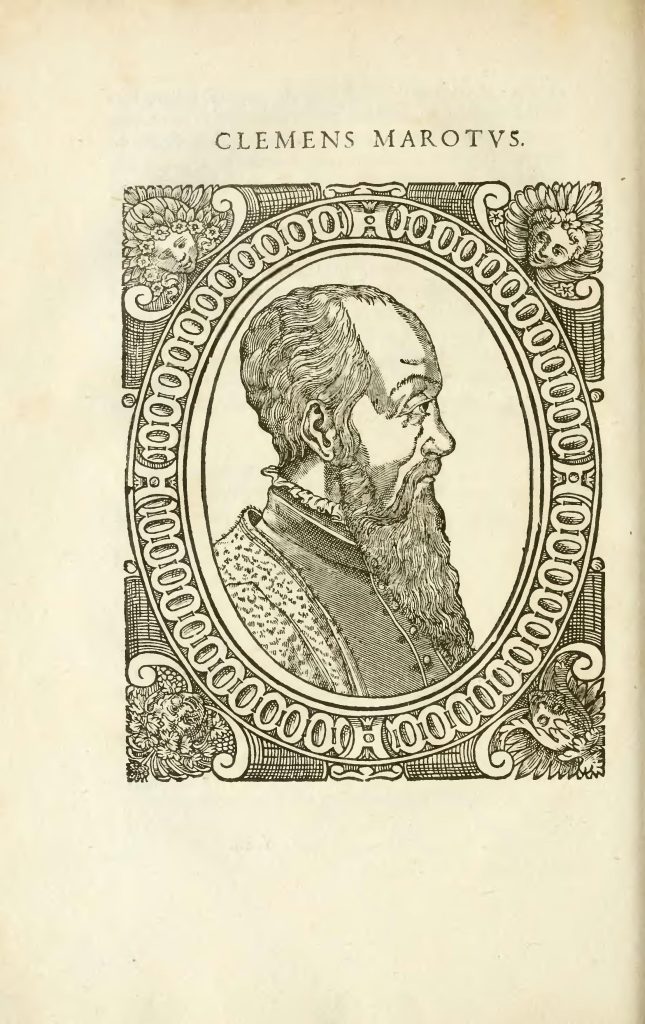

2. Frontispice in Jean de Tournes, Oeuvres 1558 (and following)

In his 1944 article about portraits of Marot, Jacques Pannier says that it is an engraving by Bernard Salomon (‘le Petit Bernard’), 1520-1570. Below a coloured version of the original imprint:

The image is very similar to Boyvin and/or the Bèze portrait. See below.

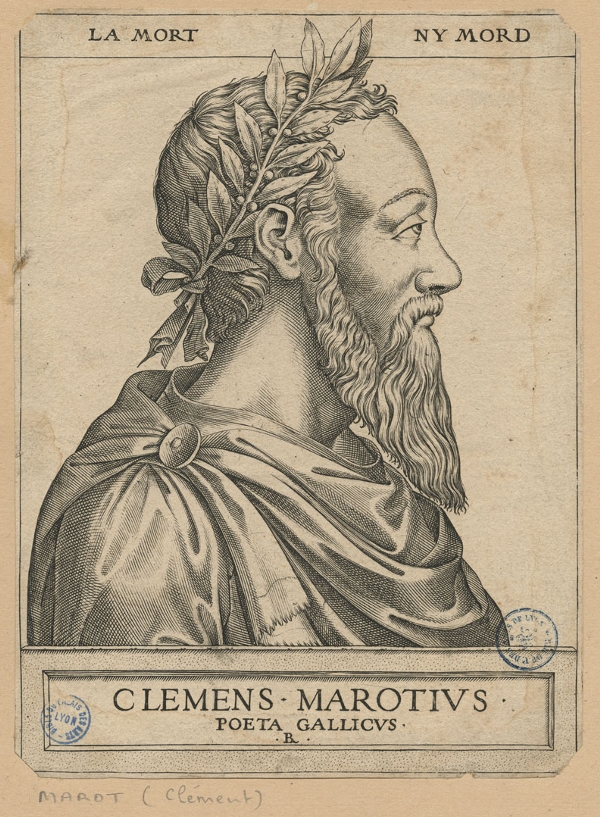

3. Engraving by René Boyvin: Clemens Marotius (1558? – and copies/variations)

Signed by René Boyvin, very small letter RB below the inscription). In the Cabinet des Estampes of the BNF (Catalogue Dumesnil VIII, Boyvin, nr. 113)

On the earliest date of this quite wide-spread engraving the article of Bentley Cranch (1985) is quite confusing. First she says it appeared in a book with ‘outstanding reformers’ (which might well be possible, see below 3b en 4). However, when she comments on the first appearance of this engraving, she refers to a book commemorating the victories of Charles V, published in Antwerp in 1558 by Hieronymus Cock (with as far as I know, heroic engravings of Charles V, by others than René Boyvin). In the footnotes she refers to the catalogue of Robert Dumesnil, Le peintre-graveur français… tome VIII (1842). There indeed four engravings are signalled; three with laurels, and one without. One is dated: 1576.

I was not able to verify/falsify the claim, because I could not find a copy of the 1558 publication (it should be on fo. 62-recto): What I could verify: In the 1556 edition the image is not present, and the topics are not at all poetry-related. Many variations on this engraving can be found, like this one flipped.

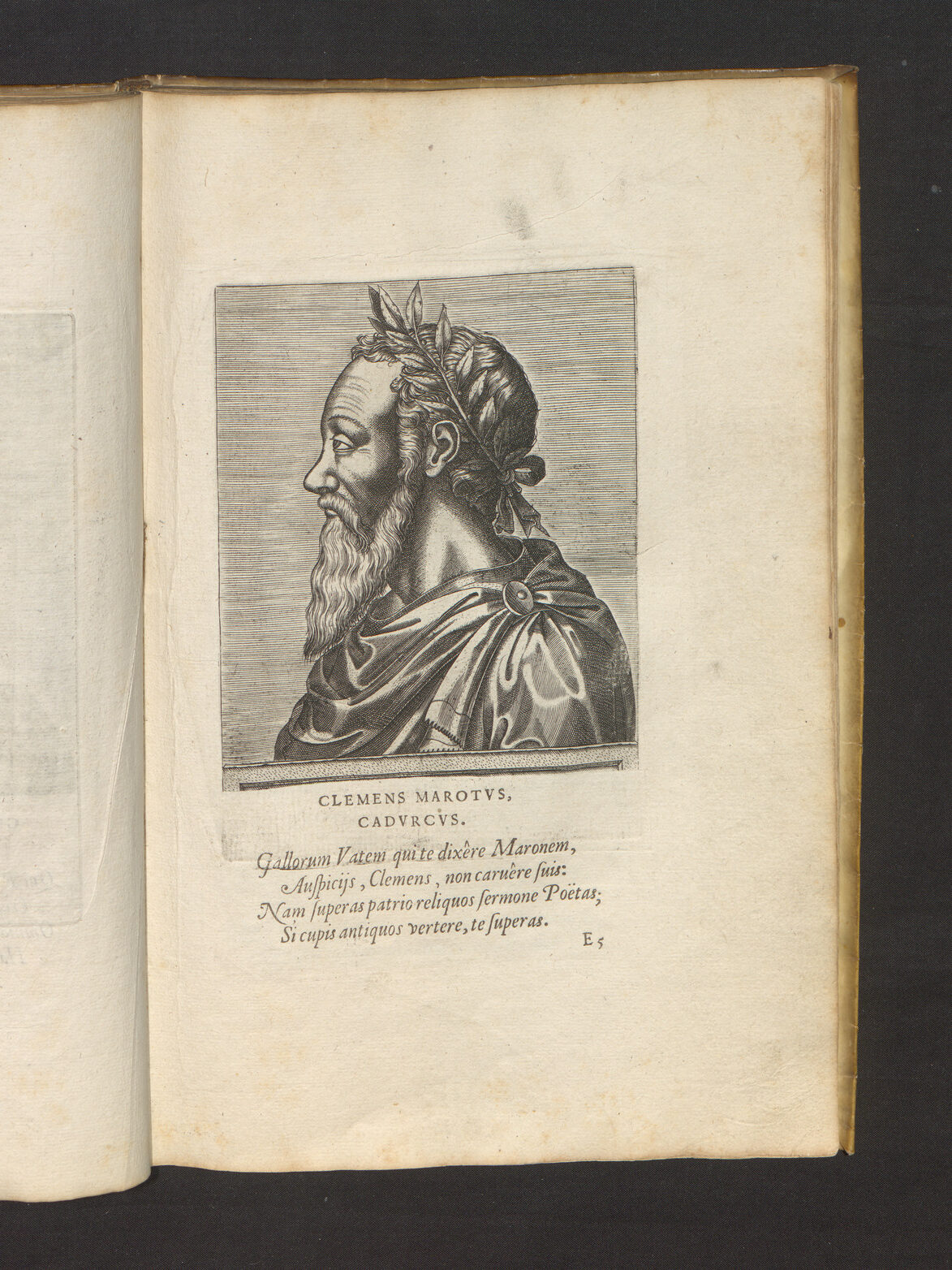

3b. Clement Marot – engraving by Philips Galle (1567/1572)

This Marot laureate was also the basis for Philips Galle’s engraving in 1572. It was published in “Virorum Doctorum de Disciplinis benemerentium Effigies XLIIII” (1567 edition lost, but engravings re-used in1572 etc…), Antwerp; The portraits have a quatrain by Benito Arias Montanus :”Gallorum Vate[m] qui… vertere et superas”. Galle used existing portraits (paintings, engravings) for his engravings.

Galle re-uses the cliché from the 1567 edition, but covers – in a first run – the engraving of the text below with a piece of paper. In a second run the new poem by Arias Montanus is printed. One can still see the upper part of the original text frame.

https://anet.be/record/opacmpm/c:lvd:6531041/N

Below the same portrait but copied from a re-issue of the same book in the same year (1572b). Marot’s name now is in a caption above (unique for this publication, but perhaps simply a correction for having forgotten to engrave the name below…). In the above-caption Marot is identified as ‘from Cahors’ (Cadurcus). The text below is changed/corrected: Vatem>Vate (accusativus>vocaticus).

The eulogy below the ‘effigies’ plays with the name of Maro (Vergilius) and Marot (quite common). I guess it says something like:

Gallorum Vate[m] qui te dixêre Maronem,

Auspiciis, Clemens, non caruêre suis:

Nam superas patrio reliquos sermone Poetas;

Si cupis antiquos vertere, te superas.

Dichter-ziener der Fransen, zij die jou ‘Maro’ noemen,

hebben geen gebrek aan passende voortekenen, Clemens,

Want je overtreft in je moedertaal de overige dichters;

Als jij je tot de klassieken wilt wenden, overtref je jezelf ook.

Poet of the Gauls, they who called you Maro,

did not lack their auspices, Clemens;

For you surpass the rest of the poets in your native language;

If you wish to turn to the classics, you surpass yourself.

[alternative: … translate the classics…]

.

4. Portrait of Marot in Béze, Icones 1581

This portrait appears next to the short biography dedicated to Marot in Beza’s ‘Icones‘ (or portraits). It might be based on the painting, supposedly owned by De Bèze (Tronchin bequest), which is shown below.

5. Anonymous portrait, from Tronchin bequest (Geneva)

This painting Museum of the Reformation (Geneva – Tronchin bequest), was supposedly once in the possession of Th. de Bèze. Argumentum: De Bèze’s adoptive granddaughter married a Théodore Tronchin. One can also ask: Is this painting the basis of René Boyvin’s engravings – or the other way around?

Note about the Hermitage portrait:

This is what Alexandra Zvereva, art historian, and specialised in 16th century portraits (courtesy Guillaume Berthon) writes about this portrait:

“Ayant travaillé à l’Ermitage, je connais bien ce dessin, qui est magnifique et, comme vous le dites très justement, assez méconnu. En ce qui concerne l’iconographie de Marot, le seul véritable portrait est le profil qui le montre barbu et les cheveux très courts. […] Le dessin de l’Ermitage montre bien un personnage âgé, barbu et vêtu comme un magistrat ou un prélat. La barrette plate est typique des années 1540. L’annotation visible en haut se compose de deux parties : à gauche “de [puis d’une main plus ancienne, écriture du XVIe siècle] chambre du Roy” et à droite “clement marot poete [d’une autre main] valet”. Les écritures à droite semblent du XVIIIe siècle. Ceci voudrait dire que le dessin était plus grand, possédait une annotation ancienne sur au moins deux lignes d’une main du XVIe siècle et uniquement à gauche. A la rognure, survenue au XVIIe ou au XVIIIe siècle, la partie découpée de l’annotation a été reportée à droite, puis complétée. Il n’y a aucune raison de douter de l’exactitude de cette reprise. Autrement dit, tout concorde pour que ce portrait soit bien celui de Marot. D’ailleurs, la barbe et les yeux un peu gros sont ceux du profil. La seule différence est le nez qui paraît plutôt busqué, alors que dans la gravure il est droit. Quant à “Du Moustier” inscrit dans le cartouche, c’est le nom apposé par le fils de Cobenzl lorsqu’il cataloguait la collection de son père. Tous les dessins de cette provenance achetés par Catherine la Grande en 1768 possèdent ces montages violets et ces cartouches avec des attributions. Pour ce dessin, le nom choisi est le seul connu à l’époque : tous les portraits français de la Renaissance de la collection Cobenzl sont attribués à un “Du Moustier” sans prénom, qui semble être Daniel, portraitiste du XVIIe siècle, plutôt que ses oncles Etienne et Pierre ou son grand-père Geoffroy, totalement oubliés au XVIIIe siècle. La manière de ce dessin ne ressemble à rien de connu. Elle est aussi très différente du portrait de Geoffroy qui n’était pas portraitiste. Pour Marot, la main n’est pas celle de François Clouet qui est le peintre du roi à l’époque. Il faut imaginer un autre artiste qu’il est impossible de nommer à ce stade.”